Many people will know of the dispute at Grunwick in North West London in the late 1970s, when a workforce of mainly Asian women took on the owner of a photo processing company who had dismissed a woman in 1976 for working too slowly. There was a lesser-known dispute at Imperial Typewriters in Leicester in 1974 when the Asian workers there struck in protest at discrimination over promotions and unpaid bonuses. Both disputes were eventually lost but at Imperial Typewriters there was no solidarity forthcoming from white workers or unions, whereas at Grunwick there was.

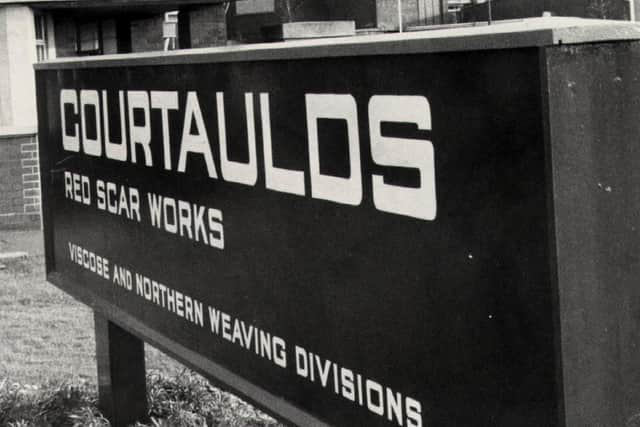

But long before these two disputes there was a strike by Black workers (Asian and African-Caribbean) at the Courtaulds Red Scar Mill factory in Preston in May 1965. Courtaulds was then a giant textiles company in what remained an important, if declining, sector of British industry. Red Scar employed 3000 workers making tyre cord and viscose. Around 1000 Asian and Caribbean workers were concentrated in the tyre cord section as a result of deliberate policy by the company. This section involved searing heat and dangerous materials which gave off toxic fumes. Many suffered eye, nose and skin complaints as a result. While white workers were regularly taken on to work there, they were then promoted to more congenial conditions while Black workers stayed for years.

The dispute occurred in an atmosphere poisoned by the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act and by the notoriously racist discourse deployed in the Smethwick by-election in 1964. The strike was sparked when the TGWU union’s regional organiser agreed a deal with management (without any consultation with the workers) in which the workers in the tyre cord spinning department, who supervised a bank of spindles on a machine, would henceforth supervise one and a half machines, rather than one, for a bonus of ten shillings per week – a 50 percent increase in output for a 3 percent pay increase. When a meeting was called to demand an explanation from the union official, he was jeered and the workers voted unanimously not to accept the deal. The implementation was then postponed but after a month, workers on the afternoon shift were faced with a faint accompli in the form of new lines of paint demarcating machines into halves and designating 1.5 per worker. The workers refused and staged a sit-in. This was followed by a walk out of all the Black workers.

The chairman of the union at the factory immediately began to sabotage the strike, by urging the workers to get back to work and by describing the dispute to the press as “unofficial and racial”. This was to be a constant element of press coverage, reporting it as essentially about immigrant workers and ‘outside agitators’ rather than about legitimate grievances over pay and productivity which the union was refusing to support. It was the union which was making the strike about race by not representing a whole section of the workforce which was in the position it was in because of management’s persistent discrimination.

The 900 strikers stayed out for three weeks but were eventually defeated. The first crack came when the 120 Caribbean workers returned to work after a talk by representatives of the High Commission urging them to display responsible behaviour. This was not the only intervention from outside; some was from those giving moral and financial support. These included leaders of the Racial Adjustment Action Society (RAAS), which advocated Black self-organisation, though not necessarily separate unions. The different approaches by the two main RAAS leaders mirrored similar differences in the US between Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton. The strike committee did indeed organise autonomously but though the workers listened to the RAAS leaders and appreciated their support and the publicity it brought, it seems clear they wanted the union to do its job of representing them, rather than wanting a separate union. Fundamentally the strike was lost because the union failed to do so; the 2000 white workers continued to work throughout. It was a shameful episode but, on the other hand, it showed that immigrant workers were capable of organising and resisting, belying the racist stereotypes of passive, compliant workers.

A prominent supporter of the tiny, newly formed International Socialists, Ray Challinor, who actively raised money for the strike fund, also wrote to MPs in support and addressed a mass meeting of the strikers. He wrote about the dispute in Labour Worker (the forerunner of Socialist Worker), identifying racist divisions as one of the most dangerous tendencies in the working class movement. This was of course only a few years before Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech. Challinor feared that the lack of solidarity between Black and white workers could even lead to separate trade unions. This may seem unlikely from today’s perspective but not at the time.

The mass strikes of the early 1970s helped to make the dockers’ support of Powell a nasty memory. But racism remains and the ugly attempts by the current government to win an election by invoking anti-migrant xenophobia reminds us that it’s a weapon that will always be eagerly seized on by the Tories and the employers.

Were you or someone you know a member of the International Socialists or Socialist Review Group? If so we would like to interview you for our project. Please contact us at contact@is-history.net.