In the first of three articles on the International Socialists (IS) and aspects of its electoral politics I looked at the tradition’s relatively consistent policy of calling for a vote for the Labour Party at General Elections. This was done through the example of the 1966 Hull North by-election. In the second of my articles I look at the short-lived experiment undertaken during the 1974-1979 Labour government of the organisation standing its own candidates.

On 20 July 1976, the IS Central Committee (CC) issued a one-page circular to all Branch/District Secretaries and Full-time Organisers titled “IS and Elections”. The circular reads as follows:

“The very rapid development of the political situation, especially the acuteness and immediacy of the cuts issue, the ferment in the Asian communities following the racist murders, and the ominous election successes of the National Party and the National Front, requires us to seek ways of strengthening our political intervention and impact.

Comrades have made a very effective anti-fascist intervention in the Thurrock by-election (as earlier in Rotherham). In Thurrock, what amounts to an election campaign has been carried out with mass distribution of literature – but no candidate.

This is excellent work, but it has one serious inherent weakness. Without a candidate, we are in a largely negative position. We are saying, ‘don’t vote fascist’ but are not, except in a very general propaganda sense, calling on workers to support some generalised political alternative. To the extent that we have an impact on voting behaviour, it is to moderate the slump in the Labour vote …

In these circumstances, we need to intervene with a complete political alternative, as well as with systematic anti-racist and anti-fascist work, so far as our resources and the possibilities permit.

The Central Committee has therefore decided that a Socialist Worker candidate will stand in the Walsall by-election … and in any other suitable parliamentary by-election … Suitability will have to be assessed on the merits of each case but includes the existence of a substantial Labour majority. The candidates will stand on a hard ‘socialist alternative’ policy and every effort will be made to draw in the support of immigrant organisations and other non-IS elements …

This is a new departure for us in practice, although not, of course, in principle. Our 1973 Conference adopted a programme which committed IS to the general line of the communist movement in Lenin’s time – which includes commitment to the revolutionary use of elections as well as a rejection of the ‘parliamentary road to socialism’. Our 1975 Conference reiterated this position whilst also deciding that an intervention in Walsall (which was already being discussed) was not appropriate at that time.

Now, with a growing Labour abstention and a significant fascist intervention, the circumstances demand a serious fight to raise the socialist alternative electorally.

We do not expect large votes. We are concerned to spread our propaganda, to broaden our circle of contacts, to strengthen links with militants – including militants in the immigrant communities, to expand sales of Socialist Worker, to recruit members and to unite the left around a militant anti-fascist, anti-government socialist platform.”

In the September 1976, Internal Bulletin the IS Central Committee explained further and more fully the change of strategy for the organisation – standing in parliamentary elections – in this case the Walsall and Birmingham, Stechford by-elections.

The rationale is explained by the CC as follows:

“Many active militants are now thoroughly disillusioned with the way this government has attacked the working class. Their anger and resentment is moving them away from the Labour Party.

In almost every part of the country there are Labour activists who put it quite starkly and say, ‘I can’t be a part of an organisation that causes unemployment and attacks the poor and the sick’.

They are moving away from Labour but not towards the Communist Party. The CP is part of the whole set up, and offers no way of fighting to change things. These militants and activists are looking for a socialist alternative.”

The CC document is at pains to point out that:

“There isn’t any way that the decision to put up candidates can be seen as a retreat from our rejection of parliamentary socialism.

Our campaign will firmly state that socialism cannot come through parliament, and it will say more.

By standing against unemployment, against the cuts, against racism, and for building a rank and file fight back, we will be saying that only workers themselves can change society.

At the same time, we have to be clear about what we expect to gain in the specific situations.

At the other end of the anti-parliamentary stick from the anti-candidate position, are those who expect IS to win a large number of votes.

We need to be just as firm about these sorts of ideas as we are about the other. The fact is, we cannot expect to win more votes than organisations like the Communist Party have gained in their campaigns …

We cannot expect to get more than a few hundred votes, and we will pick up considerably less votes than the National Front. The NF will do very much better than the SW candidates because the NF work within the stream, within the accepted ideas of the ruling class.”

The CC document ends with a list of seven aims for the by-elections around targets for membership increases, a strengthening of district organisations, sales of Socialist Worker, large contact lists, credibility within the Black community, an acceptance amongst militants and activists that SW is about building a socialist alternative and increasing our periphery nationally.

As it turned out the Birmingham, Stechford by-election was not held until March 1977 but IS (under the title “Socialist Worker”) stood in Newcastle Central on the same day as the Walsall North contest – 4 November 1976. Reports on both by-election campaigns are contained in the November 1976 IS Internal Bulletin.

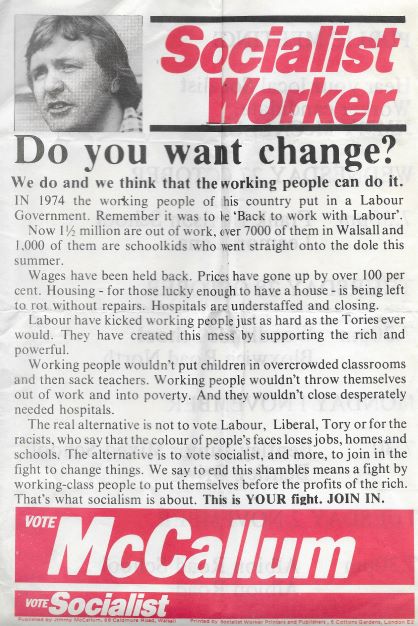

Jimmy McCallum stood in Walsall North and got 574 (1.53 percent) votes. Before the election IS had five members in Walsall, all in one factory. During the campaign seven or eight new members were recruited in Dudley and 25 in Walsall, nearly all workers. Some good trade union contacts were made during work on the estates and many good general contacts were made in the shopping centres. The addresses of 2,000 buyers of Socialist Worker were recorded.

There had been an anti-NF demo in Walsall in mid-September which IS mobilised for nationally (I remember being there myself). This helped the campaign get off to a good start and apparently, the effects on the Asian population and the left in the town was significant.

The total cost to the organisation was approximately £900.

Jimmy McCallum Walsall North

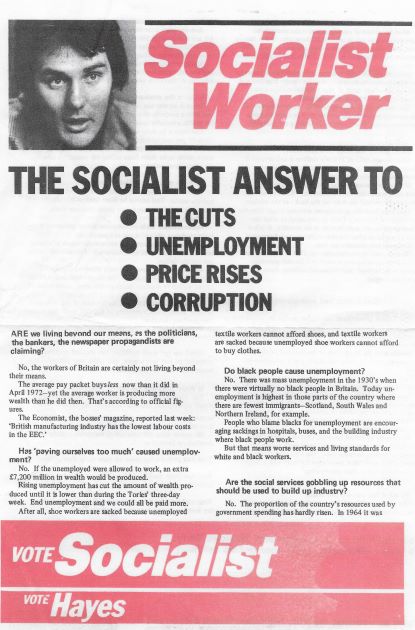

Dave Hayes Newcastle Central

In Newcastle Central the candidate was Dave Hayes and he polled 184 votes (1.87 percent). Prior to the election, the IS branch had 50 members, albeit only one lived in the constituency itself. A total of 29 recruits were made – one in the constituency and eight in Sunderland leading to a new branch there. Among the recruits were five or six shop stewards plus the first IS member in the shipyards – a chairman of the Boilermakers committee in the yards. About 70 workplaces were visited. The total cost was approximately £800.

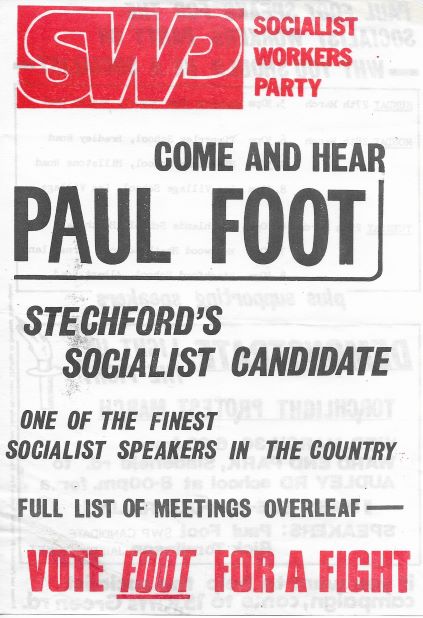

On 31 March 1977 Paul Foot stood in Birmingham Stechford and received 377 votes (1.0 percent). The local targets set for the campaign had been “Increase in membership – 15; Increase in Socialist Workers sales – 150; Beat the CP vote of 1974” and all three were achieved. Socialist Worker reported:

“[I]n all 42 Birmingham workers joined the SWP during the by-election campaign. Thirteen are shop stewards, 15 are black … In the nine days of the active SWP campaign, 1,000 SW’s were sold. This looks like settling down to a regular sales increase in Birmingham of at least 170”.

In an unexpected turn of events Paul received less votes than an International Marxist Group (IMG) candidate did. Why this happened is explained by Sheila McGregor (Birmingham Organiser) in the SWP Internal Bulletin No. 5 (June 1977) as being due to poor organisation around an anti-NF demo in the city in February.

Paul Foot Birmingham Stechford

Next, on 28 April 1977, came by-elections in Ashfield and Great Grimsby. Jill Hall stood in Ashfield and got 453 votes (1.0 percent). Michael Stanton was the candidate in Great Grimsby polling 215 votes (0.5 percent). In terms of recruitment to the SWP the figures were 25 in Ashfield and 50 in Grimsby.

In the May 1977 SWP Internal Bulletin Duncan Hallas writes on the subject of “Electoral blocs and joint slates”. The reason for the contribution is that “some comrades have asked if we should reconsider our attitude towards an electoral pact with other organisations on the revolutionary left” – for all practical purposes at this particular juncture this meant a pact with the IMG.

The long and fully argued answer from Hallas is “no”. Here is the key part of his argument:

“We are certainly in favour of joint action with everyone in the working-class movement, whether Labour Party members, CP members, independents or whatever to fight the fascists, to fight hospital closures, to fight the Social Contract and so on and so forth – always provided it is action. We do not, however, form blocs to make propaganda. We put forward our own ideas in our own paper.

The distinction is obvious enough. Unity in action with everyone who can be pulled in to support the particular action, irrespective of their views on other matters. Independent expression of our own ideas at all times. We don’t stay out of any genuine working class struggle and we don’t make our participation conditional on others agreeing with us. At the same time, we don’t hide or dilute our politics or pretend to be other than we are.

How does this apply to parliamentary etc. elections?

Revolutionary intervention in parliamentary elections at present is essentially a propaganda operation, a means of contacting people and involving them in some of our activities and of recruiting.

We judge our success (or failure) in a contest by members recruited, contacts made, SW readers gained and so on and not mainly by votes gained.

Of course, it is very pleasing if we get a better than expected vote, a little disappointing if we get a lower than expected vote. But it is not the main thing. We are not parliamentary roaders.

Even in circumstances where there is a serious prospect of winning a particular contest this remains true. It would be very useful for propaganda and, indeed, agitational purposes to have a revolutionary MP, or even better to have several.

But this will always be secondary to building the party in the workplaces, to fighting for leadership in the day to day struggles of working people and inside the unions.

Our aim in contesting parliamentary elections is to build the SWP. We do not put the emphasis on getting the biggest possible vote for the ‘far-left’.

Protest votes, and that is what is being spoken of, are not without significance, but they are incomparably less important than building the party.”

The 1977 SWP Conference passed a motion on “Electoral Strategy” confirming that the SWP “stands candidates as a party building operation” and “we will not enter into a bloc or front with other organisations”. The motion does, however, clarify the position on voting Labour when more left-wing candidates are standing. The motion ended with:

“[W]e will … call for a vote for Labour solely as against the Tories, fascists, nationalists etc, (where we have no candidate). We will not urge support for Labour, especially right-wing Labour, against more left-wing candidates and our members will be expected to vote for these. Our campaigning will, however, be for the SWP”.

On 18 August 1977 Kim Gordon, one of the organisations leading Black activists, was the Socialist Worker candidate in Birmingham Ladywood. He polled 152 votes (1.0 percent) but the IMG “inspired” Socialist Unity candidate got 534 (mainly Asian) votes and a Black Nationalist candidate got 336.

Around the end of 1977 thoughts were turning to the next general election, the standing of SWP candidates in that election and the lessons learned so far from the by-elections. An internal document “Our Election Tactics in the General Election” was produced but not widely circulated. It was signed by Tony Cliff, John Deason, Jim Nichol, Mel Norris, Margaret Renn and Jack Robertson and pointed to the failures of our current electoral strategy and the costs, financial and otherwise, of not correcting them.

The policy of standing in appropriate by-elections continued, however, into the following year.

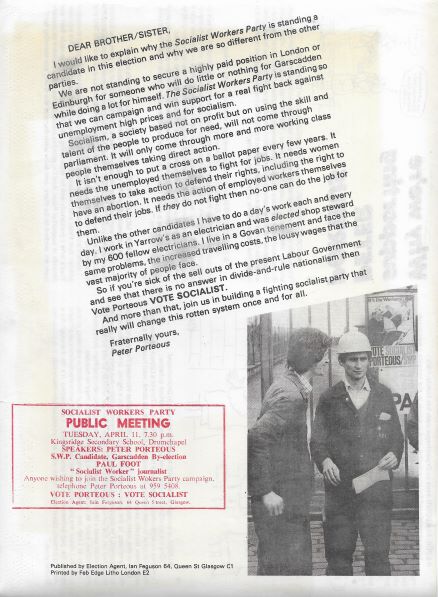

On 13 April 1978 Peter Porteous, an electricians shop steward in Yarrows Shipbuilders, was the candidate in Glasgow Garscadden. He polled 166 votes (0.5 percent), way behind the CP’s vote of 407.

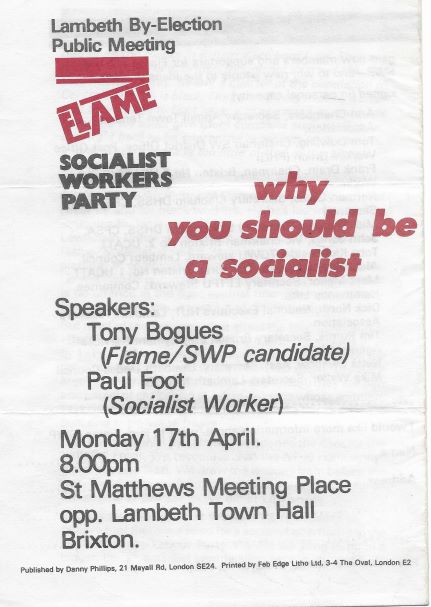

The following week, 20 April 1978, Anthony Bogues stood in Lambeth Central as the Flame/SWP candidate. Flame was “the monthly socialist paper by and for Black workers” and Tony was its editor. He received 201 votes (1.0 percent). In what might have been a final straw for the SWP leadership Tony was beaten by both the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP) and “Socialist Unity” candidate.

Peter Porteous Glasgow Garscadden

Tony Bogues Lambeth Central

Indeed, it was the final straw. Duncan Hallas produced a document dated 21 April 1978 titled “Elections – We Have to Think Again”. This later appeared in the May 1978 Pre-Conference Issue 2 SWP Bulletin in a slightly amended format as a Central Committee document called “Election Strategy”. The document opens with:

“A serious revolutionary organisation has to be able, as Trotsky once put it, ‘to look reality in the face’. It has to be able calmly to check its predictions and assess its policies against the facts that experience reveals. And it has to be able to do this, and to correct its course when necessary, without any attempt to ‘cover up’ or pretend or bluff in the interests of the ‘prestige’ of this or that comrade or group of comrades or leading committees or even of the party as a whole.

Fact one: we have not done well in recent by-elections.

Fact two: our performance in this field has not been getting better over time; if anything, it has been getting worse.

Fact three: this cannot reasonably be blamed on ‘special circumstances’. Every case is ‘special’ but the sum of the ‘special cases’ adds up to the trend – and the trend is not what most of us expected nor is it what we predicted. We have now, after all, contested eight by elections. Enough to make a realistic assessment.

None of these unpalatable facts – and they are facts – is any grounds at all for criticising the comrades who have been actively involved in election work. They have worked hard and well along the lines laid down by the organisation nationally. The fault, if there is one, lies with the CC, the NAC and Conference. There can be no question of making scapegoats of the comrades who have actually carried out the work and made recruits and contacts in the process.

But neither can we blind ourselves to the results …

… We did not go into election work primarily to get votes but we certainly did not go in to get results like this”.

Hallas continues by recapping “what we set out to do” and “what was achieved”. Hallas writes that:

“The original decision to go into electoral work had been taken with one eye on the CP. Their inactivity in this field was, we believed, due mainly to their extreme unwillingness to upset Labour MP’s. We assumed this would continue and that, in most cases, we would have a clear field, nutters apart, because our non-CP rivals on the left were also not running.

The Militant group, probably the biggest after us, were tucked away safely in the Labour Party. The IMG was half in the LP and half out and the WRP visibly declining. None of the rest of the sects was capable of intervening. The prospect was open, or seemed to be, to establish ourselves as the far-left opposition to Labour, albeit a very small one in electoral terms. We looked to a spin-off from this in other fields of work”.

According to the CC:

“Birmingham, Stechford put an end to this as a realistic perspective. We got 377 votes (100 more than the CP got in October 1974) and 45 recruits were made; in itself a good result. But the IMG (not running as Socialist Unity – they hadn’t got around to inventing that yet) took 494 votes. The total far left was a respectable 2.5 percent of the poll. But we took less than half of it”.

For the CC:

“The conclusion is inescapable. We do not enjoy dominance over the far left in the electoral field. Our original aim in this field has not been achieved and is not now achievable by simple persistence in our present tactics”.

Underlying the problem with the votes themselves was the evidence that it was proving extremely difficult to retain members recruited during the election campaigns. This was particularly the case in areas such as Ashfield, Grimsby and Walsall where, before the campaigns, we had little or no organisational presence.

The CC document then turns to “what to do now” in the light of all the learnings.

Their first conclusion is that the original aim of standing 50-60 candidates (so as to qualify for television time) in the General Election is no longer a viable tactical option. On the other hand, they state that we should not rush to the other extreme and stand no candidates at all.

The second is that during the General Election campaign the bulk of our propaganda must be aimed against the Labour government – but where there will be no candidate to the left of Labour, we will call for a Labour vote to keep the Tories out.

Thirdly, one learning from the by-elections is that there are a significant, although not massive, number of people who are prepared to vote to the left of Labour. Under certain conditions, an electoral intervention can lead these people to be drawn closer to the SWP. The conditions identified by the CC are the pre-existence of a strong party organisation operating in the constituency, the need to be ultra realistic about what we can achieve in terms of votes and recruits and there should be no splitting of the left of Labour vote.

This last point is of some interest given how one year earlier Hallas was wholly against pacts. Here Hallas (on behalf of the CC) writes:

“The gains are likely to diminish to zero where we are standing against other far left candidates. This is particularly true in the case of Socialist Unity, although it seems that even the WRP can whip us. Therefore, we must take all steps necessary to ensure that where we stand we do not run the risk of splitting the vote to the left of Labour, including seeking a non-aggression pact with Socialist Unity.”

The CC contribution concludes thus:

“Provided that these conditions are kept firmly in mind, then a limited election intervention can still be worthwhile. In practical terms, this means that we should aim to stand between ten and fifteen candidates in the general election. In the overwhelming majority of constituencies, where we will not be standing, we should call for an anti-Tory Labour vote. However, in our propaganda our fire should still be concentrated on Labour’s policies. We should avoid standing against other candidates to the left of Labour and should, where they stand, vote for them.

To sum up, we made a miscalculation when we took the original decision to stand candidates in 1976. The miscalculation has not proved disastrous, but it could do so unless we recognise our mistake. The proposals contained in this document provide the basis for a realistic alternative policy.”

The proposed change of strategy provoked a substantial debate in the run-up to the June 1978 SWP Conference with a range of views put forward. At the Conference itself the views were distilled into three alternative propositions as follows:

- Put forward by Duncan Hallas, Eddie Prevost and Andy Strouthous: Essentially:

- standing 50-60 candidates is not a serious possibility

- SWP intervention to be a propaganda one

- standing 10-15 candidates adds little – we should “withdraw temporarily from the field so far as candidates are concerned”

- a pact or alliance with Socialist Unity is no solution

- our propaganda “must be the bankruptcy of the Labour Party and the necessity to build a real socialist alternative. We should call for an anti-Tory vote. Vote left, vote Labour or cast a protest vote for candidates left of Labour, but build the SWP as the core of the fightback against Thatcher and Callaghan”

- Put forward by James Anderson, Dave Peers, Sue Cockerill, Linda Quinn and Sandra Peers: Essentially:

- our original reasons for standing 50-60 candidates remains valid today – but our success has been limited by the Socialist Unity offensive – the IMG has outflanked us

- the disunity of the left is a barrier preventing workers moving towards revolutionary politics

- a separate campaign with 15 SWP candidates does not solve the serious problem. The Socialist Unity offensive against us is mainly electoral and it is mainly through a united front electoral strategy with them that we can undercut their vague but quite significant “Socialist Unity” appeal

- we should publicly call for a strictly electoral link up which would include Socialist Unity and as many other organisations as possible from the working class and the black community

- Put forward by Peter Bain, John Cowley, Kim Gordon and Steve Jefferys: Essentially:

- we don’t believe that there will be a serious SWP intervention on our general politics if there is no direct electoral intervention

- the experience of electoral interventions is that we can build around candidates, and that when elections take place without candidates it is extremely difficult to motivate members’ SWP activities

- our activity (wages, anti-cuts, equal pay, Grunwicks, Lewisham, ANL Carnival etc) has created an audience it would be a tragedy for us not to approach in the General Election as the SWP

- we need to choose areas with large Labour majorities so that we can run a strongly anti-Labour campaign

- we support a maximum left anti-Labour vote, and therefore wish to work out non-aggression pact[s] with other left-of-Labour forces

- gains can be made for the SWP by standing a limited number of candidates. “We instruct the CC to prepare the ground in discussion with the Districts to ensure that we have at least one candidate in every major area”

As the first proposal included Duncan Hallas it can be safely assumed this was the CC’s preferred option but in the event conference passed option number three.

Actually, this was not to be the final word. The Central Committee revisited the question in the December 1978 SWP Internal Bulletin by saying that:

“… however, post-Conference, new factors emerged. First, the General Election is postponed so we have the opportunity to review the question. Second, and very important, enquiries have shown that very few districts are willing to run candidates and find the necessary money.”

Suffice it to say that SWP candidates did not run in the 1979 election.

The table below provides the full details of the eight by-elections fought by IS/SWP in the 1974-1979 Parliament:

By-elections fought by IS/SWP Candidates in the 1974-1979 Parliament

| Date | Constituency | Candidate | No. of Votes | Percentage Share | Elected |

| 4/11/1976 | Newcastle Central | David Hayes | 184 | 1.87 | Harry Cowans (Lab) 4,692 votes |

| 4/11/1976 | Walsall North | James McCallum | 574 | 1.53 | Robin Hodgson (Cons) 16,212 |

| 31/3/1977 | Birmingham Stechford | Paul Foot | 377 | 1.0 | Andrew MacKay (Cons) 15,731 |

| 28/4/1977 | Ashfield | Jill Hall | 453 | 1.0 | Tim Smith (Cons) 19,616 |

| 28/4/1977 | Great Grimsby | Michael Stanton | 215 | 0.5 | Austin Mitchell (Lab) 21,890 |

| 18/8/1977 | Birmingham Ladywood | Kim Gordon | 152 | 1.0 | John Sever (Lab) 8,227 |

| 13/4/1978 | Glasgow Garscadden | Peter Porteous | 166 | 0.5 | Donald Dewar (Lab) 16,507 |

| 20/4/1978 | Lambeth Central | Anthony Bogues | 201 | 1.0 | John Tilley (Lab) 10,311 |

| Total votes | 2,322 | ||||

| Average votes per candidate | 290 | ||||

| Average percentage | 1.0 |

What is one to make of the SWP’s electoral strategy in the period 1976-1978?

According to Ian Birchall (2011):

“Cliff was particularly enthusiastic for the electoral turn; Hallas was much more cautious. Cliff relentlessly argued his case and carried the organisation”.1

and Ian concludes with:

“The reason for failure was twofold. Other left groups were standing candidates and there was a failure on all sides to agree not to stand against each other. So, there were sometimes two and, on one occasion (Lambeth Central in 1978), three revolutionary socialist candidates in the same election. Voters could not be bothered to disentangle the differences between them.

More importantly, although Labour was doing badly in electoral terms, there was no substantial body of Labour support willing to break away to the left. Again the resilience of reformism had been underestimated. Cliff’s long-term analysis of the historical decay of reformism was certainly valid, but in the short term it did not produce the anticipated results”.

I do not personally recollect being too downcast at the time with the small votes obtained. As someone operating in an IS/SWP branch where you could spend a few hours on a busy high street only selling a handful of papers I do not recall expecting high votes. I was content to argue the line with work colleagues that we were recruiting large numbers of new members and building the organisation. To find later that those gains were only transitory was the big blow.

Note

This paper is a specially edited extract from my confidential research document:

Rudge, John. 2019. Out for the Count: The SWP and UK Parliamentary Elections, 71pp.

References

- Birchall, Ian. 2011. Tony Cliff: A Marxist for His Time. Bookmarks Publications, London 664pp. ↩︎

Were you or someone you know a member of the International Socialists or Socialist Review Group? If so we would like to interview you for our project. Please contact us at contact@is-history.net.